Executive Summary: CMS describes a National Healthcare Directory that will streamline provider data collection and promote interoperability. Years of industry engagement have produced layers of additional use cases. CMS should consider focusing on foundational data and not prematurely adding scope until it has established a complete, accurate provider demographic data set. CMS should also consider engaging with providers on platforms where they currently submit data.

Last week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) published a Request for Information on the topic of a National Directory of Healthcare Providers & Services. The RFI seeks industry feedback on the ambitious idea of creating a public directory of healthcare providers to streamline the collection of provider data to support provider search, data exchange, and other use cases. Such a directory, if successful, could eliminate $2B of administrative waste and expand the government’s push towards greater transparency and access to healthcare.

The RFI, by design, presents more questions than answers. It describes the Directory at a high-level and briefly mentions secondary use cases. The RFI then presents a whopping list of 91 questions to the industry on the potential scope, benefits, policy pre-requisites, implementation considerations, and measures of success of a National Directory. This article boils down the RFI into its key parts, contemplates how the National Directory could work, categorizes the questions presented, and offers up modest recommendations on a Phased implementation.

Opportunity to reduce administrative waste; adoption challenges ahead

Defacto Health does not offer a (strong) opinion on whether a National Directory should be established. Numerous industry bodies will respond to the RFI and offer their answer to that question in the next 60 days. We simply say: if the US healthcare data ecosystem were started from scratch, the availability of a National Healthcare Directory with complete and accurate information would reduce administrative waste and increase access to care. However, the challenges lay in transitioning industry players from the current, fragmented model to a centralized model for data collection and validation across multiple, mission-critical use cases. CMS anticipates these challenges as demonstrated by these three questions:

- “How could NDH use within the healthcare industry be incentivized”

- “How can data be collected, updated, verified, and maintained without creating or increasing burden on providers”

- “What technical or policy prerequisites would need to be met prior to developing an NDH?”

To make a National Healthcare Directory happen, many Chesterton fences will need to be inspected, moved, or torn down. Said another way, key adoption barriers must be addressed and incumbent players and workflows will be disrupted.

Problem Definition: Redundant reporting, inaccurate data, lack of interoperability

All that said, CMS is seeking to solve very real problems that have plagued the healthcare industry for years and where innovators have made incremental progress, but nothing that has transformed the way the industry works. The leading problems that CMS describes, and believes a National Directory could solve, include:

- Redundant reporting/data submission from providers

- Lack of interoperability

- Directory and Endpoint data inaccuracy

CMS cites studies and agency audits that quantify the cost ($2.76B annually) of redundant submission from providers, data inaccuracy (45%, 55%, and 49% of payer-listed locations had at least one deficiency), and lack of interoperability (2.9M NPIs without digital contact information). CMS posits that a National Directory could alleviate these issues.

Defacto’s view on pre-conditions for a National Healthcare Directory to be successful in solving these problems:

- A National Directory could alleviate redundancy and cost in data submission IF industry players (including payers and government agencies) stop using current channels to collect directory data.

- A National Directory could promote interoperability IF incentives/benefits exist (high quality and/or comprehensive data) or enforcement requires healthcare industry participants to consume data from or submit data to Directory.

- A National Directory could improve data accuracy IF it established a standard for accuracy, measured it continuously, provided feedback to attesters, and published those metrics out to the industry.

Solution Hypothesis: “A Centralized Data Hub” could streamline data collection and dissemination

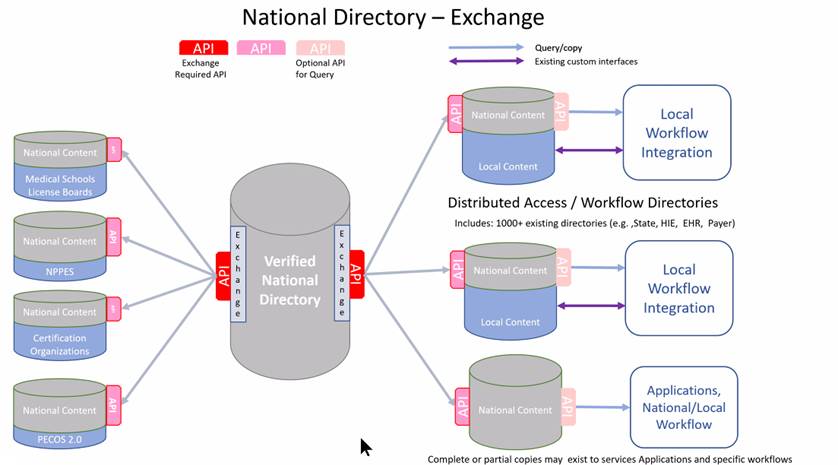

CMS offers clues as to how a National Directory could operate. What follows is a summary of CMS’s description of the solution in the RFI combined with information described in the referenced HL7 Implementation Guides:

- Centralized Data Hub – A single place for providers to deposit information, and for others to get the it.

- API-enabled (FHIR) – CMS describes APIs as part of its outbound distribution mechanism for the data, but there may be a role for ingestion of the data from primary sources as well.

- Directory information – They leave the full scope of data flexible, but mention name, address, phone number, specialty, and hours. Also mentions institutions (hospitals, nursing facilities) and suppliers and pharmacies.

- Digital Contact Information – They mention FHIR endpoints and Direct Addresses

- Validation – They leave it flexible but mention primary source verification and attestation.

- Public facing CMS portal – For consumers and others to access the Directory

- Security and Privacy controls for sensitive information

Attribution: National Directory Exchange and Query https://confluence.hl7.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=139664322

A reference implementation of the National Directory was built for demonstration at a recent Connectathon. The reference implementation ingested data from NPPES, inserted it into a database, and produced data in a queryable format. Its scope is a small fraction of the functionality, data, and inter-system interaction required of a National Healthcare Directory. There has been no single industry platform that has attempted to address the vast scope of the National Healthcare Directory, and so attempting to architect something that supports such diverse use cases has inherent risks.

National Healthcare Directory Use Cases Considered

CMS also mentions several use cases that a National Healthcare Directory could support. These are listed in order of emphasis and mentions within the RFI itself:

- Finding and selecting healthcare providers

- Facilitate interoperable provider data exchange

- Payers, providers, and others identify each other’s digital contact information

- Help payers improve accuracy of their directories

- Public health reporting

- Coordinating patient care

- Provider referrals

- Prior authorization requests

- Fraud, waste, and abuse prevention

- Licensing, certification, and credentialing

Where did all of those use cases come from?

The list of use cases finally described in the CMS RFI is long, and there are even more use cases contemplated in the Implementation Guides. The tendency for a Directory solution concept to attract additional use cases is natural given the generic (non-use case specific) nature of Directory as a product concept (i.e., a list of searchable information of a particular type). Is a Directory a phone book or an address book? Should you be able to search a Directory by category (e.g., the type of provider)? Should you be able to get other information (e.g., digital contact information) about a Provider in the Directory? Should you be able to get information about the Provider’s endpoint? Should you be able to get information about entities other than Providers in the Directory? Should you be able to look up the relationships between Providers and those other Entities? Should you be able to use any of this information for a diverse range of use cases by diverse constituents? Each one of those ‘shoulds’ is reasonable in a vacuum, but in the aggregate, introduces layers of complexity and risk.

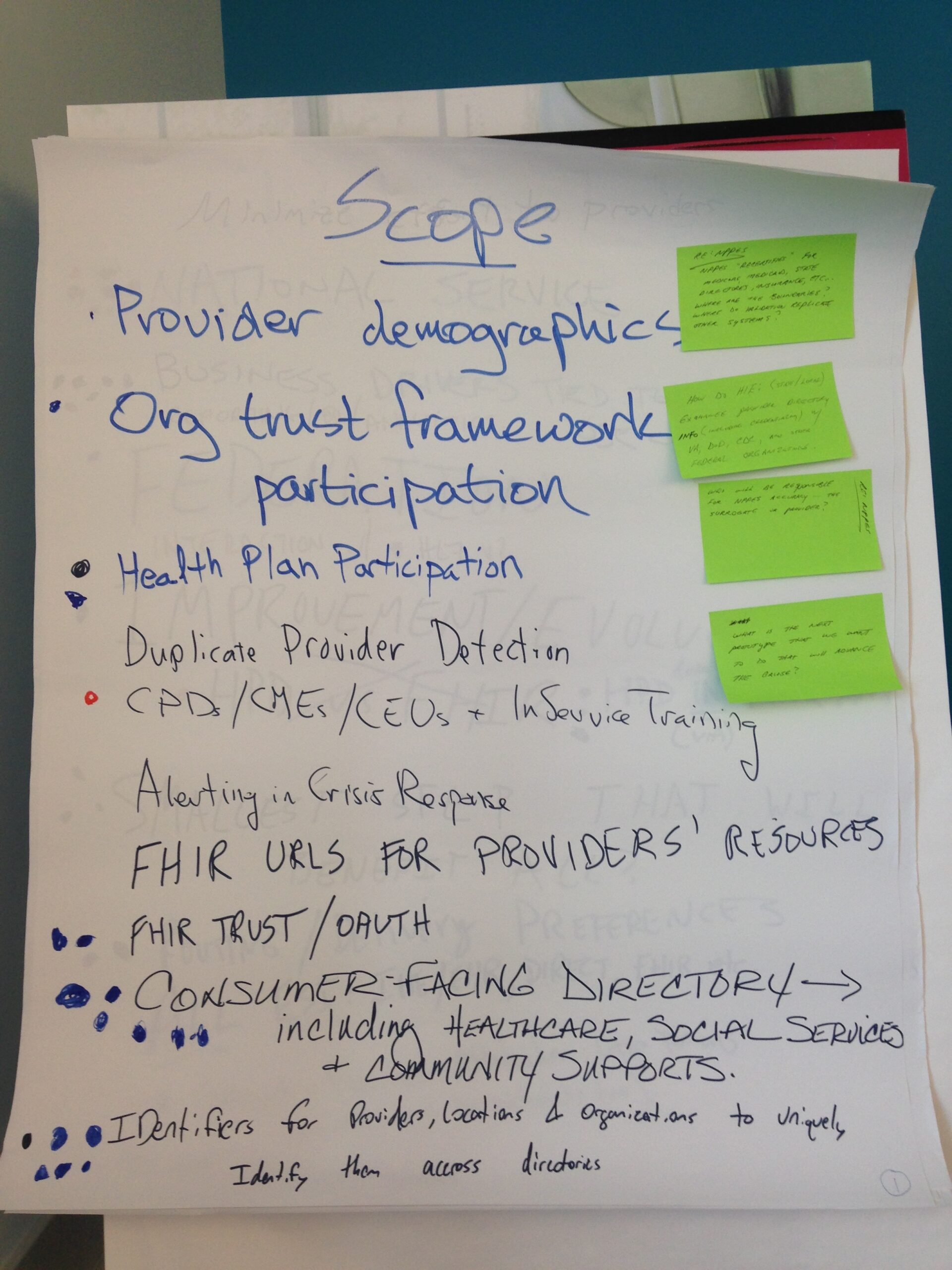

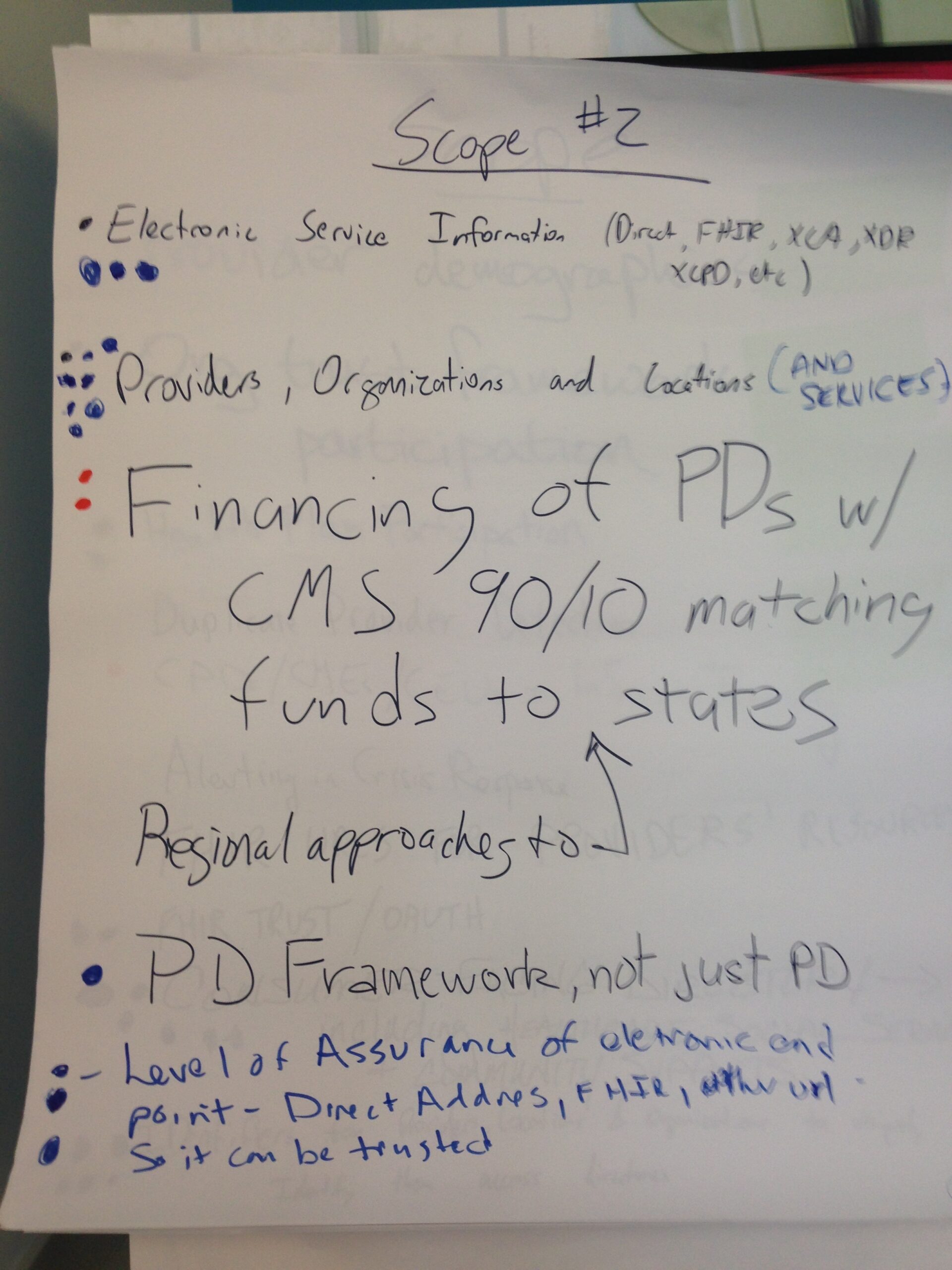

This is how the conversation emerged in the 2016 Workshop hosted by ONC and FHA in Mclean, Virginia. ONC did an excellent job of inviting a cross-section of healthcare industry participants: payers, providers, clearinghouse, HIEs, software vendors, not-for-profit associations, standards bodies, and government officials. On day 2 of the Workshop, ONC led a few collaborative sessions to elicit ideas on what a National Directory could do. The first part of the session was characterized by participants from different parts of healthcare (e.g., a payer and an HIE) talking past each other on what a directory should do (“a directory is for finding a provider v. a directory is for finding a provider’s endpoint to exchange data”). Some understanding was established, some trust was forged, and the ideas started sticking to the wall. What you see below are two mega post-its that were used to capture use cases from these participants and their dot votes on the priorities of these use cases. There are nine of these post-its with a diverse range of use cases (e.g., provider demographics, data cleansing, provider endpoints, provider search, trust frameworks) that reflect some of the diversity that you see in the CMS RFI itself.

Three years later, the sequel to the Workshop was held in Washington D.C. By 2019, multiple attempts had been made to create state or national utilities to solve Directory-related problem(s), in reaction to a wave of regulatory and legislative activity promoting provider directory improvement and interoperability. There was an increased focus in the 2019 ONC workshop on topics like governance, enforcement, funding, and incentives to participate. Attendees in those workshops collaborated on analysis and research that would be incorporated into the Validated Healthcare Directory (VhDir) Implementation Guide, which is referenced by the CMS RFI. Three other Implementation Guides have since been authored on the topics of Endpoint Querying, Attestation, and Data Exchange. An ‘base’ Implementation guide is in the works.

CMS asks 91 questions to seek industry feedback on the National Healthcare Directory

Many of the issues and challenges identified in the ONC meetings on a National Healthcare Directory remain. CMS acknowledges this and is not shy about describing the issues and proactively engaging industry with a list of related questions. Defacto Health has prepared a matrix of question categories, and whom it thinks could best respond to them.

| Category of question | Sample of Questions (not all 91 represented here) | Whom best to respond? |

| Interaction with other CMS systems (NPPES, PECOS, etc.) and state and local systems | 1. What benefits and challenges might arise while integrating data from CMS systems (such as NPPES, PECOS, and Medicare Care Compare) into an NDH? 2. What data elements from each of these systems would be important to include in an NDH versus only being available directly from the system in question? 3. Are there systems at the state or local level that would be beneficial for an NDH to interact with, such as those for licensing, credentialing, Medicaid provider enrollment, emergency response (e.g., Patient Unified Lookup System for Emergencies (PULSE)73) or public health? | System owners in CMS Other Federal Agencies Government Contractors/Systems Integrators State Medicaids, and other State HHS agencies |

| Scope of Data and Use Cases | 1. What functionality would constitute a minimally viable product (MVP) for a NDH? 2. What provider data elements would be helpful to include for use cases relating to patient access and consumer choice (e.g., finding providers or comparing networks)? 3. We want an NDH to support health equity goals throughout the healthcare system. What listed entities, data elements, or functionalities would help underserved populations receive healthcare services? Are there use cases to address social drivers or determinants of health? 5. Would there be benefits to include public health entities? 6. Are there use cases for which an NDH could be used to help prevent fraud, waste, abuse, improper payments? 7. What data elements would need to be included to support licensing, certification, and credentialing? 8. What use cases would benefit from data being verified and what sort of assurances would be necessary for trust and reliance on those data? | Payers Providers HIEs, QHINs Other Federal Agencies (DoD, VA, CDC, FDA) Life Sciences companies Software vendors Other Solution Providers Industry associations (CAQH, AHIP, AMA NCQA, Joint Commission, URAC, MGMA) Patient Advocacy Groups |

| Adoption Drivers or Barriers | 1. How could NDH use within healthcare be incentivized? 2. How could CMS incentivize payers, health systems, and public health entities to engage w/ NDH? 3. What technical or policy prerequisites would need to be met prior to developing an NDH? 4. What specific strategies, technical solutions, or policies could CMS employ to best engage stakeholders and build trust throughout the development process? 5. How can data be collected, updated, verified, and maintained without creating or increasing burden on providers and others who could contribute data to an NDH, especially for under-resourced or understaffed facilities? 6. How could consistent and accurate NDH data submission be incentivized within the healthcare industry? | Payers Providers Industry associations (State Association of Health Plans, State Medical Societies) State-based Provider Directory Initiatives Distributed ledger initiatives experimenting with incentives-based marketplaces |

| Success Measures and Likelihood | 1. How could CMS evaluate whether NDH achieves targeted outcomes (e.g., that it saves providers time or that it simplifies patients’ ability to find care)? 2. Would an NDH provide the benefits outlined? 3. Would an NDH as described reduce the directory data submission burden on providers? | Industry Associations Patient Advocacy Groups State Governments Payers Providers |

| Interoperability | 1. How could a centralized source for digital contact information benefit providers, payers, and others? 2. Beyond FHIR APIs, what approaches should be taken to ensure that directory data are interoperable? 3. How can we associate group- or practice-level digital contact information with appropriate providers to ensure that data get to the right place? | Payers Providers HIEs, QHINs Recognized Coordinating Entity Interop Vendors Software vendors Clearinghouses |

| Operational Factors | 1. What are some of the functions or features of current provider directories that work particularly well? 2. What policy or operational factors should be considered for data collection interfaces as a single point of entry? 3. What are current and potential best practices regarding the frequency of directory data updates? 4. What specific strategies, technical solutions, or policies could CMS implement to facilitate timely and accurate directory data updates? 5. How should duplicate information or conflicting information reported from different sources be resolved to balance reporting burden versus data accuracy? | Payers Providers HIEs, QHINs Software vendors Other Solution Providers State-based Provider Directory Initiatives |

Defacto Health recommendations: Start focused and prove value, meet providers where they are

Defacto Health will provide a response to CMS through the official channels, but for the purposes of this article, we will answer four of the questions CMS posed in the RFI:

- What functionality would constitute a minimum viable product?

If CMS decides to move forward with a National Healthcare Directory, it should focus on a single use case, and achieve unparalleled success in a key performance dimension. For example, CMS could decide to establish a single market pilot to centrally collect provider directory data and set a goal to achieve > 80% provider participation, > 80% accuracy, and > 80% of payers ingesting data from the utility. If it can hit the trifecta of supply-side participation, demand-side participation, and high quality, it will be an initiative that cannot be ignored, and the industry would want to see replicated elsewhere.

- What specific strategies, technical solutions, or policies could CMS employ to best engage stakeholders and build trust throughout the development process?

CMS should be clear on the immediate goals and use case(s), set clear performance metrics around them, and be transparent in how it is performing against those metrics. The RFI and previous collaboration work has uncovered a trove of use cases, however, it is important for this utility to unambiguously solve one problem for the industry, before prematurely moving on to the next one. As was realized after the launch of Healthcare.gov, a key success factor for large scale government IT systems is ‘ruthless prioritization’. A directory is hired by its users to ‘do a job’, and that job needs to be clear. CMS should also engage not only with the practitioner community, but also the administrative staff supporting them to manage and submit their data. Focused analysis and understanding of the ‘user journey’ and the data supply chain will clarify whether a National Directory can achieve intended goals.

- How can data be collected, updated, verified, and maintained without creating or increasing burden on providers and others who could contribute data to an NDH, especially for under-resourced or understaffed facilities?

To avoid creating ‘yet another channel’ and inadvertently increasing administrative burden, CMS should consider meeting providers where they are and take advantage of data they already entered . There are industry-operated platforms, voluntarily adopted by most payers and providers, that have much of the data that CMS is seeking to collect as part of a National Healthcare Directory. It could be possible to collaborate with those platforms to have an opt-in allowing the data to flow into a National Directory. This would accelerate adoption of the Directory and minimize additional burden on healthcare providers. Standards-based data exchange (made possible by CMS Rule on Patient Access and Interoperability) and use case-focused Implementation Guides make this model more feasible now compared to a few years ago.

- What use cases should be prioritized in a phased development and implementation process for immediate impact and burden reduction?

If CMS decides to move forward, it should first work on baseline provider demographic data (that which is required and audited by Medicare Advantage), establishing the most comprehensive, accurate, and used repository of that data. Digital Contact information and other use cases build on top of the foundational Demographic data. Not getting basic information correct would erode trust in a Directory’s ability to address future use cases. CMS can always present use cases on a multi-year roadmap and should be clear on decision gates and success criteria to move from one phase to the next.