Special thanks to Aneesh Chopra, Chief Strategy Officer at Arcadia; Ryan Howells, Principal at Leavitt Partners; Eric Ellsworth, Director of Health Data Strategy at Consumers’ Checkbook; Matthew Robben, Chief Technology Officer at Serif Health; Brendan Keeler, Interoperability and Data Liquidity Practice Lead at HTD; and Chris Schwartz, Senior Product Manager at Healthgrades for reviews and input.

Closing the Consumer Experience Gap

As the Trump administration begins its second week, the transition period presents an opportunity to reflect on our nation’s progress in healthcare interoperability, to revisit the foundational principles behind key policies, and consider the path forward. Many of these initiatives were designed with the goal of improving the patient experience, and there has historically been bipartisan support for this objective. Significant strides have been made in the past two decades —EHR adoption goals have been achieved, payers and providers are implementing government-required APIs and machine-readable files, payers, and providers are expanding data exchange use cases, and TEFCA is establishing a common trust framework for data exchange. More stakeholders are embracing standards and operating on the same shared rails for healthcare interoperability.

However, despite this progress, a gap persists between expectations and the reality of the consumer healthcare experience. Challenges remain, including misalignment between industry stakeholders and issues with data openness, completeness, and accuracy. In this post, we will explore four critical areas—plan selection, provider selection, patient data access, and price transparency—and propose strategies to build on the advancements achieved thus far. In the following table, we review the key policies that addressed these use cases, alongside timely quotes from the Presidents who championed their implementation:

| Patient Use Case | Relevant Policies |

| Health Plan Shopping | “It’s a website where you can compare and purchase affordable health insurance plans, side-by-side, the same way you shop for a plane ticket on Kayak — same way you shop for a TV on Amazon.” Barack Obama, 2013 Affordable Care Act 2010: Created online marketplaces for consumers to shop and compare health insurance plans. Created transparency around directories and formularies. 21st Century Cures Act 2016: Authorized CMS and ONC to require APIs of providers and payers, and restricts providers and health IT vendors from ‘information blocking’. |

| Health Care Shopping | “Our goal was to give patients the knowledge they need about the real price of healthcare services. They’ll be able to check them, compare them, go to different locations, so they can shop for the highest-quality care at the lowest cost.” Donald Trump, 2019 CMS-1717-F Hospital Price Transparency Final Rule 2019: requires hospitals to publish negotiated rates in machine-readable files. CMS-9915-F Transparency in Coverage Final Rule 2020: requires health plans to publish negotiated rates in machine-readable files CMS-9115-F Interoperability and Patient Access Final Rule 2020: requires health plans to publish provider directory data via APIs |

| Avoiding Surprise Bills | “No one in America should be bankrupted unexpectedly by health care costs that are absolutely out of control. No family should be blindsided by outrageous medical bills.” Donald Trump, 2019 No Surprises Act 2021: Protects patients from surprise bills from out-of-network providers in in-network facilities, and enables Good Faith Estimates and Advanced Explanation of Benefits to provide clarity on costs before receiving care. |

| Patients Accessing and Using their Data | “No longer will Americans spend hundreds of dollars on redundant medical tests or countless hours collecting copies of their medical record, which are often still transferred using a fax machine or CD-ROM. Americans will finally be able to control their health record.” Press Secretary for Donald Trump, 2020 “By computerizing health records, we can avoid dangerous medical mistakes, reduce costs, and improve care.” George W. Bush, 2004 CMS-9115-F Interoperability and Patient Access Final Rule 2020: requires health plans to allow patients to access their data via APIs, and to be able to authorize third-party applications access to APIs and data ONC Cures Act Final Rule 2020: requires healthcare providers to allow patients to access a subset of their data via APIs, to authorize third-party access to apps “without special effort”, and to export all of their health information in a machine-readable format |

Two decades of policies across three presidential administrations laid the foundations for interoperability infrastructure. A combination of enabling legislation, executive orders, agency rules, and, most importantly, payment reforms increased the transparency of healthcare prices, provider networks, and patient data. This data was supposed to make it easier for patients to shop for care, shop for plans, and access their own data, on their own, or via a platform they trust. Health insurers and providers spent billions of dollars on interoperability, much of which built upon public investment and more broadly, focused on complying with government requirements.

Healthcare providers and insurers alike appeared to focus more on implementing these requirements, rather than responding to payment reform signals that would value how these APIs and data sets would be used by their own developers, or in collaboration with the public and designated third parties. While an initial set of use cases were described in government rules and implementation guides, it was unclear whether demand for those use cases would emerge from consumers. Ironically, APIs required for third-party access were discovered by internal stakeholders within healthcare organizations seeking to build and use a longitudinal patient record. In the midst of this uncertainty, healthcare IT leadership and their vendors focused primarily on compliance rather than ensuring that such infrastructure could be meaningfully used by consumers. This resulted in the availability of a narrow set of clinical and administrative data in hard-to-use APIs and machine-readable files, with no associated performance standards to match emergent and scaling demands. Fundamentally, the developer ecosystem fell short of the possibility to incorporate this data into applications that met the needs of patients to make better decisions on plan selection, provider selection, appointment booking, and cost estimation.

The ideal healthcare experience for consumers remains elusive. It is still difficult for patients to compare health plans in terms of their provider networks, benefit design, estimated out-of-pocket costs, or their relative user experience (beyond customer satisfaction surveys). The switching costs are high, and the information is insufficient to give consumers confidence that a new plan will be favorable from either a financial or care perspective. Finding an in-network provider remains a challenge due to directory errors, ghost networks (providers listed in a payer’s directory but who are not in-network or who are otherwise unavailable), and ambiguous plan and network names. Getting a timely appointment is difficult due to provider shortages and opacity around appointment availability. By the time a patient books an appointment, the patient must answer questions on a clipboard about their healthcare history and insurance that they’ve likely answered tens of times before. Finally, requesting clinical notes, imaging, and other important information from the appointment can be challenging for the average patient. The patient experience has yet to materially improve. This YouTube video that comedically asks what if ‘air travel worked like healthcare’ was posted 15 years ago. The patient experience problems that it satirizes are still with us today!

Wherefore art thou, ‘Expedia for Healthcare’?

When travel shopping websites like Expedia and Kayak launched in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the American public viewed them as a revelation. They suddenly made shopping for flights (and hotels and rental cars) easier, more transparent, and empowered consumers to find and book services. Zillow had a similar impact on real estate in the mid-2000s, allowing unprecedented access to publicly available, though less easily discoverable home value data. These consumer-centric websites acted as the ‘counteracting institutions’ that bridge the ‘quality and uncertainty’ chasm described in George Akerlof’s 1970 paper ‘The Market for Lemons’. They reduced information asymmetry, allowing markets to function better and consumers to make better choices. It is no wonder that policy makers, in the following two decades, alluded to such shopping experiences to cast a vision for how key healthcare decisions can be simplified for millions of Americans. There existed the idea that advancements in information technology and expanding adoption of the Internet could similarly enhance the healthcare experience.

How healthcare is different

Healthcare is not travel. Healthcare is not real estate. Professionals who have worked in healthcare technology and/or healthcare policy for years view these analogies as overly simplified and imperfect. Let us explore the differences between healthcare and other verticals, as the differences help explain why the best efforts of the public and private sectors have been unable to produce such an Expedia-like experience for healthcare consumers to date.

- Weak economic incentives (consumers) – Insured patients are insulated from the direct impact of healthcare costs as the insurer often foots the bill, in particular for consumers with low deductible health plans. App developers seeking to navigate consumers to higher quality, lower cost services lack sufficient economic incentives to promote adoption. Promising approaches, such as tools enabling consumer gainsharing when selecting high-value care, lack widespread adoption by employers. For consumers, it is also true that purchasers of airline flights are more cost-conscious, as they are paying for their flight entirely out-of-pocket, versus a healthcare consumer. However, there is a large percentage (~40%) of insured individuals on high deductible plans, and there is an emerging trend where some states (TN and TX) allow patients to opt to pay cash (when the price is lower) for healthcare and count towards a deductible. These types of consumers are going to be more cost-conscious, if they are able to know their costs. A 2022 survey showed that while 64% of Americans have not shopped for healthcare by price, 58% said they would if information was disclosed ahead of time. Consumers are motivated to shop for healthcare if tools were easier to use.

- Weak economic incentives (payers and providers) – As noted earlier, payers and providers are primarily implementing APIs and machine-readable files to comply with regulatory requirements. Without strong patient demand for APIs, the payers and providers will implement the minimum functionality required, and dedicate limited attention to factors like data accuracy, performance, and discoverability. This creates a classic ‘chicken and egg’ dilemma: consumers are unlikely to adopt solutions until they present a strong enough value proposition. However, the value proposition will not exist until the APIs function and the data is correct. Industry appears to be waiting for a breakthrough ‘killer app’ (akin to a healthcare version of Zillow’s ‘Zestimate’ or Priceline’s ‘Name Your Price’) that presents immediate value to consumers. Demand for that app would drive demand for APIs, increase focus on data quality, and unlock adjacent use cases through better interoperability. Could such a ‘killer app’ ignite a healthcare interoperability flywheel?

- A priori v. posteriori decisions – A priori means ‘by deduction’ and posteriori means ‘from observation’. A consumer looking for a flight knows what they’re purchasing: a flight from origin A to destination B on a certain date. On the other hand, a patient deciding on a healthcare provider may not be able to deduce the exact services provided to them, as the provider often decides this during the appointment (i.e., after the patient has already selected the provider and booked the appointment). This makes it difficult to shop based on price, as the patient knows her ‘chief complaint’ but may be unsure of the clinical diagnosis and even less sure of the treatments the doctor will order. This concern applies both to primary care referrals as well as to consumers wishing to exercise their rights to a “Good Faith Estimate,” which we will unpack more later.

- More data is needed from more parties – Launching Expedia required working with the airlines themselves to access networked data on flight (and seat) availability and costs. This was a challenge, but a challenge in aggregating one type of data from one type of organization. In healthcare, you need varied data from payers (directory, coverage rules, rates) and providers (appointment availability, panel availability, services available). The relative complexity and diversity of healthcare services is also greater than travel-related services. This increases the complexity of getting the data correct, complete, and joined to make health care shopping possible. Zillow may be a better analog for healthcare than Expedia as it required data from real estate Multiple Listing Services, banks, municipal property and tax systems, schools, and open data initiatives.

- Less underlying infrastructure exists for data exchange – The SABRE system had already been established for travel agents in the 1960s, and dial-up services like CompuServe and Prodigy already tapped into SABRE in the 1980s. SABRE was the perfect platform with fit-for-use data. It was used for appointment bookings and ticket purchasing, so appointment and pricing data were accurate. Expedia built on an existing platform and rode the secular trend of Internet adoption in the 1990s and 2000s to bring self-service airline booking to more people. Healthcare is more fragmented than the airline industry and real estate. There is no single platform, nor industry consensus data standards, like in travel (or even, a federation of hundreds of listings platforms like in real estate) that manages all available healthcare appointments. There is also no openly accessible directory that serves as a source of truth, nor one that can aggregate provider updates such as with basic information about their location, their contact information, or their accepted insurances.

US healthcare is indeed different from travel, real estate, or other verticals that are often compared. The Expedia analogy was always more of a ‘this is how consumers wish to shop for care’ statement rather than a ‘let us employ the same playbook’ statement. The ideal healthcare experience is more complex, and requires more infrastructure building, coordination, and clever incentives to succeed. The underlying premise of data transparency and technology empowering consumers to make better choices is still valid, and we should not interpret industry differences as meaning it is impossible to create an Expedia-like experience. We need to approach the problem with respect for its complexity, as the interoperability infrastructure that healthcare lacks will need to be fully built out.

Transparency expands, but data quality and standardization are lacking

While point solutions for each of these problems exist, there has been limited industry adoption, and nobody has integrated all of these capabilities together into a single pane of glass, across all lines of business, and across all healthcare industry players. The primary beneficiaries of transparency data and APIs are currently healthcare organizations rather than patients. Payers and providers use price transparency data to support contract negotiations with each other. Payers and life sciences companies leverage provider directory data to better manage provider networks and optimize provider outreach. While patients remain the gatekeepers for their data via the Patient Access APIs operated by both providers and payers, most patients are not yet using the APIs, third-party apps, and their own data to inform healthcare decisions. While more transparency helps the industry become more competitive, patients are still unable to access the ideal patient experience. What stands between patients and the ideal experience that this newly transparent data was supposed to enable?

We can think of the recent transparent price, network, and patient data and APIs as ‘raw ingredients’ for a truly streamlined patient experience. These data and APIs need to be refined and integrated to be ready-for-use by third-party apps. The quality and availability of the data exposed by these machine-readable files and FHIR APIs needs to improve, so that components can be easily combined by innovators. This will necessitate the existence and prevalence of join keys across data sets (e.g., provider identifiers, network identifiers, and plan identifiers), and parameters to query by those identifiers. To promote innovation in industry, these workflows must be built by a combination of first-parties (e.g., payers and providers with direct access to their data) and third-parties (who access the data via standard-based APIs and machine-readable files, with patient authorization where necessary). The ideal experience will only be possible with standards-based data exchange, across organizations, and where APIs and data are built to support key patient use cases. Third-party innovation around externally accessible APIs and data sets will serve as a necessary catalyst to accelerate compliance and innovation by first party healthcare incumbents.

Incentives exist, but they need to be unlocked

More work needs to be done to incentivize robust implementation of APIs and data infrastructure to support these use cases. Lack of enforcement could be improved by exploring more streamlined testing and monitoring of APIs and machine-readable files. Third-party developers are willing to share test scenarios, test results, and ranked lists of payers and providers that are best complying with these rules. Public testing utilities like Inferno have been created and can support conformance testing. Government agencies should leverage that information wherever possible to streamline the monitoring and enforcement of requirements.

Beyond compliance, however, it is important for payers and providers to see intrinsic value in making these APIs and data available. One area where this could be true is in the exchange of data between payers and providers. For many of these APIs, business-to-business data exchange is a secondary use case, however, seeking value out of these APIs for those business-to-business use cases may yield efficiency advantages and tangible ROI. For example, payers are using other payers’ Provider Directory APIs to assess where they stand in a geographic market relative to network competitiveness. Similarly, providers and payers are beginning to notice each other’s Patient Access APIs to access clinical data on shared patients. In fact, CMS-0057F will require a provider ‘flavor’ of the Patient Access API, and require payer-to-payer data exchange. These APIs could be a more efficient mode of data transfer versus outdated, manual chart chases for quality, risk adjustment, and value based care use cases. By 2027, providers will be able to access payers’ Prior Authorization APIs to determine documentation requirements, and to more efficiently transact prior authorizations. As payers and providers seek to increase interoperable data exchange with one another, the quality and completeness of these APIs and data will improve for patient use cases as well.

Providers and payers are also exploring how these APIs can be used by themselves, as a first party, to share data with patients through trusted, designated apps. Finally, plans and employers could increasingly deploy decision tools to consumers and employees that will present a gainshare benefit to them, when they make better decisions. As plans and employers seek to use APIs and data to steer members, their interest in data quality increases, and implementers will follow suit. First party interest (by providers, payers, and employers) in these APIs and apps will raise the sea level of quality and availability of these APIs for third-party developers and innovators.

What could ‘Expedia for Healthcare’ look like?

When these data sets are ready, a consumer will be able to find the right provider, who is able to provide the care they need, who is nearby, who accepts their insurance, who has available appointments, and at a predictable and fair price. If the patient chooses, they can opt to have their data from either their current plan or provider to inform additional provider selection (bringing in historical data on the care they received, medicines they take, and their conditions). The patient may also choose to use this data to pre-populate information in a digital clipboard in a doctor’s office, simplifying the arduous check-in process. This data can support plan selection, informing which plans include preferred providers and with a range of estimated out-of-pocket costs that the patient can expect. Finally, this data can support post-appointment care, as patients can bring their data into personal health tools. Patients will be able to make healthcare decisions with more confidence, and supported with complete, accurate, and contextually-relevant data. Fair and affordable providers and plans will be selected resulting in the emergence of a more dynamic and competitive healthcare ecosystem.

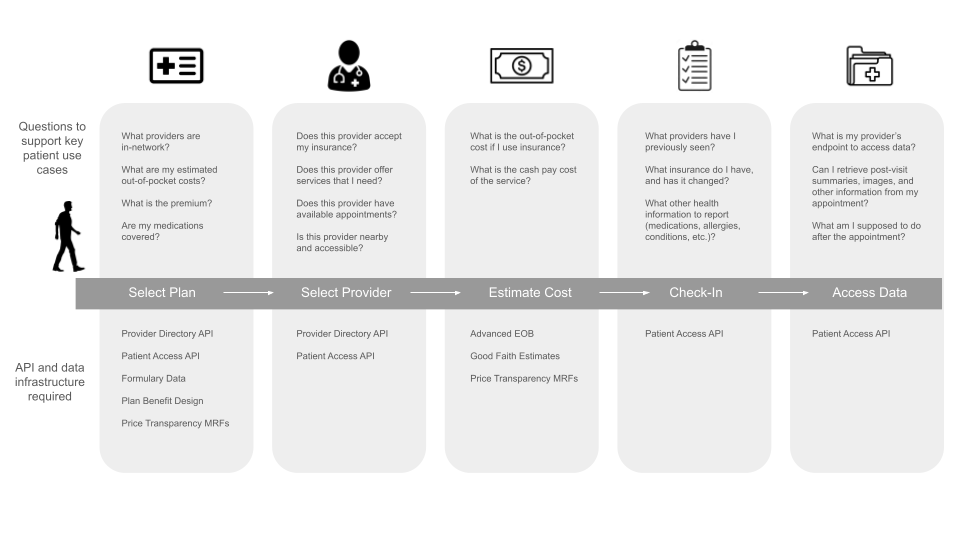

Figure 1 – Patient Use Cases, Key Questions, and Data/APIs Required

What specifically in the data needs to improve? We will go into detail on a per ‘use case’ basis. In general, the issues are of data availability, quality, and completeness. In terms of availability, there are still many healthcare providers and payers that are out of compliance with one or more of these transparency or interoperability requirements. Flexpa’s November 2024 ‘State of Patient Access API’ report and Defacto Health’s July 2024 ‘State of Provider Directory API’ report show a long tail of payers needing to comply with API requirements. In November 2024, the HHS Office of Inspector General found that 37% of hospitals did not comply with price transparency requirements. The ASTP also has observed ‘information blocking’ among healthcare providers. Government agencies have been slow to enforce these requirements on payers and providers. Incomplete participation means incomplete data which constrains the search space for patient-facing decision tools. In addition, data quality issues can reduce consumer confidence in these tools and data. There are also cases where it is unclear whether the payer or provider has published all their available data. The job of standards in policy (e.g., required USCDI and US CORE in CMS-0057F) has primarily focused on defining content and exchange data formats, and conformity with those formats. Real world experience with FHIR and other standards suggests there is room for improvement in those areas but also in the quality and completeness of the data. One potential avenue is defining ‘performance’ standards: does the data accomplish the job of the use case as defined in policy (e.g., Is an endpoint discoverable? Can I connect without special effort? Are these providers in-network?). Payers and providers need to grasp the ‘ideal’ experience that patients expect, how this required data supports those use cases, and ensure that the data is fit-for-use. Industry leadership and governance is required to make this happen.

A roadmap of industry recommendations

What we will do in the next sections is review specific data requirements, the anticipated patient uses for the data, and what improvements we must see for those uses to be realized. These can be thought of as ‘cheat sheets’ for regulators, industry associations, and implementers as they build on previous work to realize the next phase of interoperability. We will not be able to unpack all of the technical details of the recommendations, but we will summarize the headline benefits, and then link to papers, implementation guides, and demonstrations that illustrate how solutions can work, and how they can scale to solve key data issues.

Provider Directory

Uses: This data helps patients select in-network providers and also helps patients select health plans where their providers are in-network. It contains information about healthcare providers, which plans they accept, their specialty, location, and contact information. Appointment APIs could eventually help patients search for providers by availability and directly book appointments.

Rules and Requirements: CMS-9115-F requires health plans funded by Medicare and Medicaid to publish Provider Directory APIs to make this information available. Previous requirements under ACA require plans on the federal marketplace to publish machine-readable directory data. Commercial network data is not yet required nationally.

Key Limitations to Address:

- FHIR APIs are not performant/scalable enough for real-time bulk requests

- Commercial network data is not universally required or available

- Provider directories are inaccurate (providers not practicing at a listed address, phone numbers not used for appointments, providers may not accept the listed plan)

- APIs lack appointment availability and booking capabilities

- Plan and network identity are ambiguous, with similar sounding plans and networks

- Insurance-aware provider look-ups are unavailable in many third-party doctor search workflows and not widely available in plan selection workflows

- Lack of universal adoption of NPI across all providers

Potential Solutions:

- Require commercial plans to publish Provider Directory APIs

- Provide guidance to payers to publish bulk FHIR Provider Directory APIs

- Define a universal standard for provider directory accuracy, measure and publish the accuracy of every payer’s directory, and impose incentives and penalties

- Require providers to publish machine-readable directory data in schema.org format alongside demographic and contact information on their own websites. This addresses three needs: provider websites are better optimized for SEO, directory data is derived from the correct source and is fit-for-use, and payers and others are able to get access to the right information directly from source.

- Require NPI to be included for every healthcare practitioner and organization in APIs

- Establish a universal network ID to represent unique networks

- Streamline the effort for providers to submit directory information to payers by establishing a National Directory and creating intelligent import capabilities

- Explore the use of identity providers like CLEAR and ID.me to maximize the impact of a National Directory ‘profile’ across diverse provider and enrollment portals.

- Require providers to publish standards-based appointment search and booking APIs. Build on the work that the Department of Veterans Affairs as they are expanding the availability of directly bookable providers for their Community Care program. Argonaut has previously authored Implementation Guides to support this, and these should be revisited and updated to support the next generation of appointment scheduling.

How This Will Improve Patient Experience:

- Patients will be able to more confidently select a provider, either in their payer’s directory or in third party workflows, that is in-network and nearby.

- Patients will be able to sort on providers who have available appointments.

- The true availability/adequacy of a provider network can be measured.

- Patients will be able to more confidently assess the relative robustness of different health plans, choosing the plan that offers the best network for them.

- These workflows will be available across all insurance lines of business.

Price Transparency, Good Faith Estimates, Advanced Explanation of Benefits

Uses: This data helps patients to understand the expected cost of care for providers before making an appointment. For the uninsured, hospital price transparency files and Good Faith Estimates can show the cash pay price. For the insured with high-deductible plans, negotiated rates will help them understand their out-of-pocket costs. In some states (Texas, Tennessee), patients can also opt for cash pay rather than insurance, and these payments will count towards deductible. For those opting to use insurance, Advanced Explanation of Benefits, produced by payers and providers, will calculate the expected out-of-pocket cost for covered services.

Rules and Requirements: CMS-9915-F requires group plans to publish negotiated rates, and CMS-1786-FC requires hospitals to publish chargemaster and negotiated rates. Public Law 116-260 No Surprises Act 202 requires providers to produce Good Faith Estimates, and payers to produce an Advanced EOB.

Key Limitations to Address:

- Limited enforcement and compliance by payers and providers

- Data accuracy and completeness issues – missing NPI lists, facility fees, codes

- Unnecessary data redundancy – conflicting or ambiguous rates for the same EIN/NPIs for the same codes making it difficult to know what ‘the rate’ is for a service

- Zombie rates – rates for services that providers do not actually provide

- Lack of universal network identifiers to map rates to a patient’s plan

- Inability to associate coverage rules to a patient’s network

- Rates in transparency files are too granular (at the code level), and it is unclear to consumers what services and items make up a typical episode of care

- Enforcement discretion exercised for Advanced EOB until standards are established

- Providers cannot produce GFE that include services by providers outside of their organization. Data exchange standards must be established.

- Lack of consumer-intuitive service bundles for which costs can be estimated

Potential Solutions:

- Greater monitoring and enforcement for non-compliance

- Open data accuracy evaluations and issue (i.e., ticketing) reporting system

- Require payers to provide explanations for conflicting rates

- Require payers to produce a ‘usage’ file to accompany rates files, that show the volume of specific services in-network providers have done, to help filter out zombie rates

- Require network identifiers that can be used as a join key between TiC, Provider Directory, Patient Access, and other APIs and data sets

- Standardize on care bundles used in an ‘episode grouper’ as defined in Project Clarity

- Conduct a real-world pilot for GFE and Advanced EOB data exchange

- Finalize payer-provider data exchange standards for GFE and Advanced EOB

- Operationalize patient request capability for Good Faith Estimate. Require the creation of an API that allows a consumer to initiate a Good Faith Estimate request.

How This Will Improve Patient Experience:

- Uninsured and high-deductible plan patients can more confidently shop for a provider based on price, and realize lower out-of-pocket costs

- Patients will be able to receive an out-of-pocket estimate before the appointment, minimizing surprises due to billing after care has been provided

- Employers can incentivize their employees to select lower cost providers

- Data can be used to support direct contracting between employers and providers

- Contracted rates will increasingly be embedded into care decision tools

- Variability in pricing for services will decrease, making prices more predictable

- Industry will align on consumer-intuitive care bundles, enabling easier comparisons of cost across hospital and payer machine-readable files

Patient Data

Uses: With the advent of APIs, patients can access more data, with less friction, and more control over how it is used. Patients can use their data to streamline the appointment check-in experience by pre-populating digital clipboards with known data sourced from APIs and mastered in a patient profile. Patients can also make relevant patient data available to providers ahead of the appointment to streamline care during the appointment, supporting more efficient and accurate diagnoses. Patient data can also be imported into health plan selection and provider selection workflows to inform better plan and provider selections. Personal care management tools can leverage payer and patient data to support health and wellness routines.

Rules and Requirements: CMS-9115F requires a patient access API from payers. ONC Cures Act Final Rule requires a patient access API from providers.

Key Limitations to Address:

- Regulatory coverage – Greater than 50% of Americans subscribe to plans that are not required to have a Patient Access API. Patients receiving care from providers with non-certified EHRs also do not have a Patient Access API from their providers.

- Lack of enforcement and compliance – Many provider and payer APIs are unavailable

- Portal registration and logins are burdensome – Patients have a difficult time keeping track of their various URLs, usernames, and passwords.

- Developer registration with APIs is non-standard and opaque

- Discoverability of APIs is lacking as there is no national directory of endpoints

- Lack of conformance to regulatory standards and implementation guides

- Unclear error codes for eligibility of patients attempting to use APIs

- APIs are unavailable across all lines of business (i.e., commercial)

- Refresh tokens – refresh timelines are often too short

Potential Solutions:

- Establish data quality standards for specific patient access use cases

- Increase compliance monitoring and enforcement

- Public testing of data for completeness and accuracy

- Identity providers like CLEAR or ID.me to simplify portal and API logins

- Adoption of Digital Insurance Cards by payers

- Data aggregation and reconciliation workflows – patients can import longitudinal data from multiple providers and payers and master it in a personal profile

- API testing utilities like Inferno to test the readiness of APIs

- Individual Access Services (IAS) across all QHINs using a single identity credential

How This Will Improve Patient Experience:

- Patients and their caregivers can access more of their data

- More patient data can be incorporated into personal healthcare tools, empowering patients in their day-to-day care and maintenance

- Patient data entry for check-in, plan enrollment, and other workflows will decrease, and the precision of search results and recommendations will improve.

Next Phase of Interoperability: Empowering Patients

As the second Trump administration considers its policy goals related to healthcare interoperability, we encourage administration officials to build on top of previously established interoperability infrastructure to fully realize the ideal healthcare experience for patients. This will require increased enforcement of established interoperability requirements with a focus on how well the data and APIs practically support key patient use cases. It will also benefit from the introduction of new requirements that support adjacent patient use cases where natural incentives do not exist for industry players to address these patient use cases independently.

There is an opportunity for public-private partnership to establish clear expectations on data usage, quality, and completeness for these patient use cases. The administration should listen to the observations from third-party developers who have firsthand experience with payer and provider APIs and data sets, to understand the limitations of the current data and what changes need to occur. This feedback will echo many of the recommendations documented within this article. Once use cases and ‘performance standards’ are defined, accountability structures need to be established across organizational and functional domains that prioritizes the patient experience and their jobs-to-be-done. The oversight around data and infrastructure usability needs to be robust, with scalable methods of conformance assessment, and the ability to highlight industry best practices and success stories.

Both government and industry need to look at the patient experience in its totality and ask ‘are patients able to get the job done?’ with the data, API, and workflows that have been created. Can patients use the data to a) pick a plan, b) pick a provider, c) book an appointment, d) understand their cost of care, e) check-in to an appointment, and f) easily access their own data? Unwavering focus on the patient experience needs to be a priority as policy is created, requirements implemented, and solutions launched. Providing such leadership to the industry will promote a more competitive healthcare ecosystem that will result in greater access to timely, low-cost, and high quality care.