Last week, a class action lawsuit was filed in the Southern District of New York against Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, accusing the health insurer of knowingly including errors in its provider directory for Federal Employee Health Benefit (FEHB) plans. The suit focuses on three plaintiffs’ challenges, caused by the provider directory errors, in accessing in-network mental health care. The complaint argues that Anthem was aware of the errors and still published its provider directory for use by its members. It further claims that Anthem violated federal and state requirements, including provider directory provisions in the No Surprises Act, Public Health Services Act, and ERISA. If it is certified as a class action, the case could impact all FEHB members who attempted to access mental health services using Anthem’s provider directory since 2018.

‘Secret shopper’ provider directory studies supporting legal action

The outcome of the case may not be known for years, but a trial could set a legal precedent if the court rules in favor of the plaintiffs. If the suit results in a favorable outcome for the plaintiffs, it could create a litigation template for members of other health plans who are challenged to access in-network health care. Integral to the complaint are the results of a ‘secret shopper’ study to simulate the experience of the plaintiffs using Anthem’s directory to seek in-network mental health care. The study conducted by plaintiffs’ counsel follows a model established by CMS in its Medicare Advantage directory audits in 2016 and by audits conducted by Senate Finance Committee members to support its 2023 hearing on mental health ‘ghost’ networks. These audits, while requiring time and effort to conduct, require no proprietary data as the information is published on payers’ public directories. That is, it is possible for any member of the public to conduct these audits.

Legal actions against payers for the provider directories have been a mix of government and consumer-initiated actions. In 2015 and 2016, California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) fined both Anthem and Blue Shield of California for inaccurate Covered California directories. A 2018 $23M class action settlement with Blue Shield of California was the consolidation of multiple consumer-initiated lawsuits. Time will tell whether the recent Anthem lawsuit is indicative of a trend towards litigation, however, we are already seeing websites like ClassAction.org recruit health plan members across all payers who have encountered ‘ghost’ networks.

Why mental health?

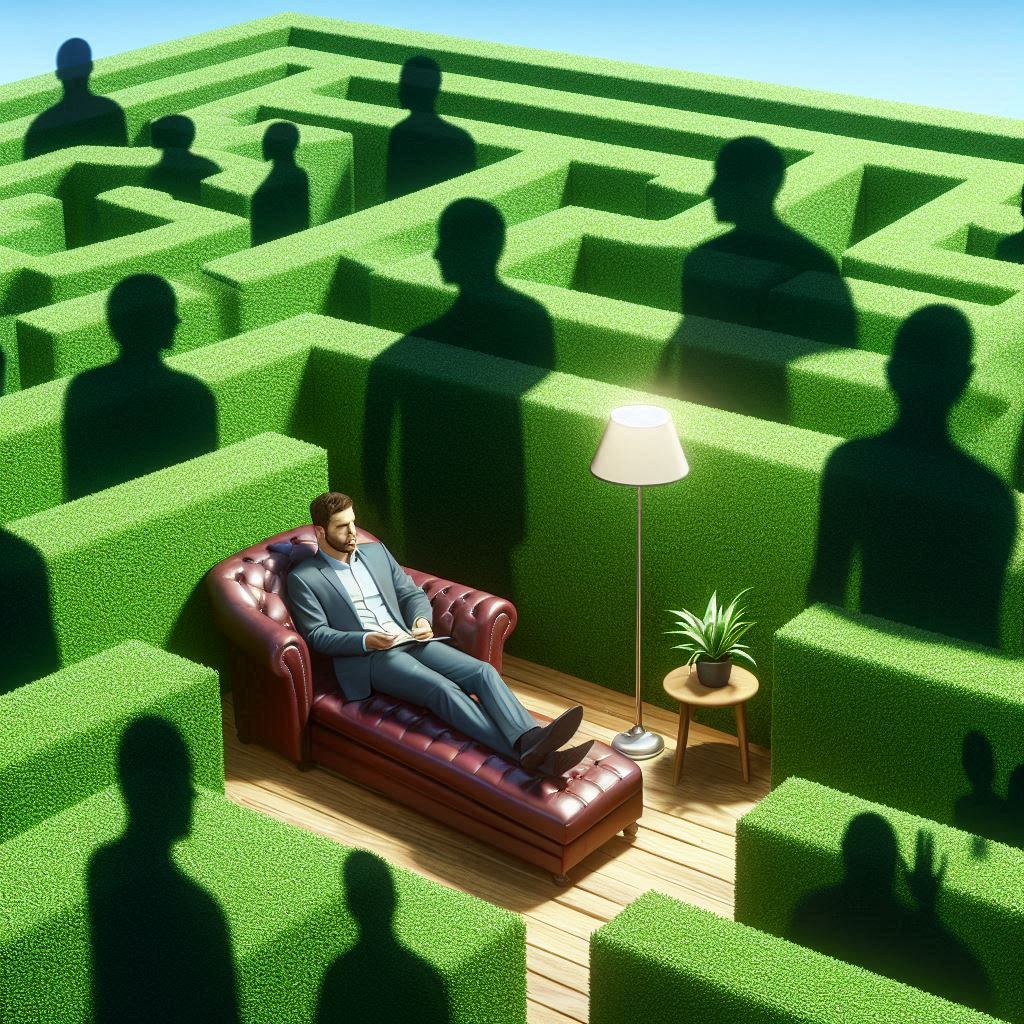

Mental health has been an opportunistic target for legal action since there simultaneously exists an increased demand for mental health and limited workforce to provide the care. A 2022 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation and CNN revealed that 90% of Americans believe there is a “mental health crisis” nationwide. According to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), there will be an growing shortage of mental health care workers across nearly every specialty by 2036. A study by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found that 27 million Americans with a mental illness are not receiving the treatment they need. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics anticipates that mental health-related jobs will grow three times faster than the average U.S. job over the next decade. Combine increased demand and limited workforce with a preference among practitioners for cash-pay patients, and it follows that patients seeking in-network care are challenged to find it. While there are provider directory errors across all specialties (prevalent among hospital-based specialties), mental health directory errors are felt more acutely by plan members due to increasing demand. It makes sense that legal action related to provider directories has focused on mental health care and that payers have become the unfortunate ‘caught in the middle’ target for public frustration.

The need for regular, ongoing directory risk assessments

Payers have made significant investments in improving directory accuracy, with CAQH estimating in 2019 that the industry spends approximately $2.76 billion annually on directory maintenance. Yet, despite this level of spend, directory inaccuracies persist. While some directory vendors claim they can deliver over 90% accuracy—and some payers report directory accuracy as high as 99%—Defacto’s assessment of payer directories shows a different picture: the best-performing payers achieve about 70% accuracy, with most payers clustering between 40-60%.

This discrepancy raises questions: if vendors are producing accurate data, is it reaching the directories intact, or are inaccuracies introduced along the way? Multiple channels and processes may inadvertently reverse corrections or allow outdated data to overwrite accurate information. A strategic chokepoint is essential where data is validated and cleansed before it reaches the directory. Furthermore, the data should be assessed in the context patients and auditors encounter it, ensuring true end-user accuracy. A third-party audit function would hold data vendors (and payers’ data ETL teams) accountable, accurately assessing risk and comparing it with other payers. Payers can use traditional methods, like their own “secret shopper” call centers, or consider solutions like Defacto Health’s API-based, score-driven directory risk reports to more quickly and frequently assess the accuracy of their directories.

Expanding access to mental health services

As payers’ directories increasingly reflect their true network, and they are able to truly assess patient access to care, payers should consider options to expand access to mental health care:

- Recruit more mental health providers: Expanding the network with additional mental health professionals can help reduce shortages and improve access for members. Defacto’s data set of 130+ payers’ network data can support payers in expanding their networks.

- Optimize virtual care options in the directory: Ensure that directory workflows are streamlined for members seeking virtual care, clearly identifying providers offering virtual-only services. Additionally, payers should advocate for network adequacy and provider directory requirements to evolve to count virtual-only providers towards network thresholds.

- Cautiously integrate AI to support the mental health workforce: While AI is being considered to help support mental health practitioners expand their capacity to see patients, it’s crucial to implement these tools with oversight. AI solutions should align with clinical needs, avoid potential bias, maintain patient privacy, and enhance rather than replace human care.

In light of the increased risk of litigation around provider directories, payers should employ scalable methods to frequently assess the risk related to provider directory errors. Measurement should occur on a regular basis, and data quality improvement interventions proactively checked against these measurements. In parallel to data efforts, and since the cause of the mental health ‘directory’ issue is only partially related to directory accuracy, payers should consider ways to expand access to mental health care. Doing so will further reduce the risk of litigation.