Yesterday at Health Datapalooza, CMS announced its intent to pilot key components of a National Directory of Healthcare in the state of Oklahoma. The National Directory RFI was released in 2022 and the use cases contemplated in the RFI were expansive, including provider search, plan comparison, care coordination, health information exchange, and public health reporting. A range of industry stakeholders, through official responses, encouraged CMS to focus on a subset of use cases and to demonstrate success locally before scaling up. It is encouraging that CMS seeks to demonstrate the value of a NDH with the Oklahoma pilot, focused on establishing a statewide centralized directory solution for qualified health plans (QHP) with the goals of increasing accuracy, reducing administrative burden, and supporting data exchange. If the pilot is successful and CMS can scale its impact at a national level, administrative processes totaling an annual $1.1 billion could be significantly streamlined.

At Datapalooza, Defacto Health participated in a breakout session on ‘National Directory for Healthcare Data Commons’ to show how public data sets could be used to support National Directory goals. We worked with mimiLabs, CareJourney, and other companies to show how machine-readable data is being used to power healthcare provider search and provider directory cleansing efforts. Defacto views public data sets, including data from Provider Directory APIs, as building blocks that can be used in the foundation of a National Directory, in its pilot stage and at scale. Consumers need to know important information about providers when selecting them, including their area of practice, their specialty, their location, contact information, availability, and the insurances they accept. Much of this data can be sourced through public data sets, though pre-processing and refinement needs to occur before it can be ingested and presented within a National Directory.

While payer directories are a ‘source of truth’ for some of this information (e.g., insurances they accept), it is widely known that the data within these directories have accuracy issues. The most recent published audit from CMS was in 2018, but ad hoc audits by congressional staff also occurred in 2023 around the time of the Senate Finance Committee Hearing on ghost networks. Most payers still have directories that are about half inaccurate and issues include providers not practicing at a location, the listed phone number does not work, or the provider is not accepting new patients. Payers have attempted numerous technical and human-intensive interventions to fix the problem with only modest improvements in accuracy. At Datapalooza, CareJourney and Marshfield Clinic demonstrated the possibility of embedding structured, Schema.org-conformant data within the same practice web pages where location and contact information are presented to patients. Aneesh Chopra asserted that providers themselves should be the source of truth for directory information and presenting machine-readable data alongside practice website data could help ensure this. Defacto agrees with this perspective, with the qualification that the data needs to be sourced from the same systems that support their web sites and find-a-doc features on their web sites. The data needs to be the same data supporting appointment scheduling and booking (i.e., patient access use cases) and not data that only supports enrollment and payment use cases.

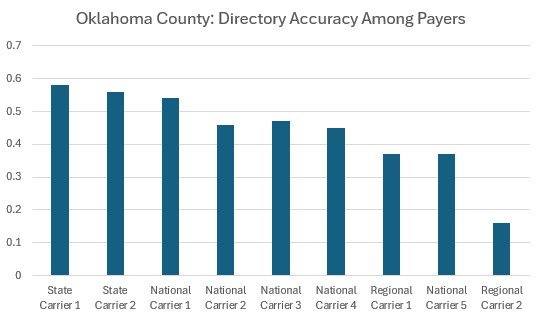

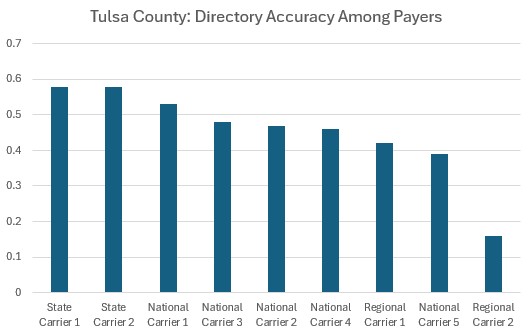

There is an opportunity to leverage the data from the hundreds of payers that have been mandated to publish FHIR Provider Directory APIs. A December 2023 HHS report encouraged the use of machine-readable data to identify errors in payers’ directories. Defacto’s article last month delved into the mechanics of using consensus algorithms to predict accuracy by seeing where payers agree and disagree on provider practice addresses. To commemorate the announcement of the NDH pilot in Oklahoma, Defacto used this methodology to conduct an analysis of the top 9 payers directories in Oklahoma to rank their accuracy within two counties: Oklahoma and Tulsa. In addition, Defacto identified the 6 provider organizations contributing the most errors to payers directories in those counties. We conducted these analyses to assess the current state of Oklahoma directories, quantify the work to be done, and identify opportunities to get it better within a pilot timeframe.

Results: Payer directories by accuracy

We masked the identities of the carriers but characterized them as either National, Regional (if they had business in more than one state, but not all states), or State (if they primarily had business in one state). For consistency we referred to the same masked name for a carrier across each county ranking.

We observe that state-specific carriers have relatively better data than national carriers. We hypothesize that this is because they can focus their provider outreach efforts and may have stronger local relationships with their provider network to support high quality information collection. We have observed this pattern in other states where we have conducted similar analyses. In Oklahoma, the national payers generally keep the same accuracy and ranking across the counties. There is a wide range of accuracy, with the top payers almost reaching 60% and others mostly hovering around 40% or 50%. Nationally, even the top performing payers are at most 66% accurate. It would be interesting, as a follow-on study, to survey these payers on their data sources, vendors, and data governance practices to see which of these interventions yields the best accuracy outcomes for payers.

Results: Provider organizations contributing the most errors

We decided not to mask the names of the provider organizations because a) providers are not currently being held liable for directory accuracy errors, and b) we understand they are not fully responsible for the accuracy of their data appearing in payers’ directories. We assessed the contribution of errors that each provider organization was associated with and prepared this listing:

Oklahoma County: Provider Organizations Contributing the Most Errors

| Provider | Practitioner-Location Count | Average Record Accuracy |

| OU Health | 4,910 | 35% |

| Saints Medical | 2,939 | 34% |

| SSM Healthcare | 1,937 | 33% |

| Integris | 4,266 | 35% |

| Zuhdi Transplant Physicians | 949 | 44% |

| Oklahoma Heart Hospital | 1,050 | 28% |

Tulsa County: Provider Organizations Contributing the Most Errors

| Provider | Practitioner-Location Count | Average Record Accuracy |

| St. John (Ascension) | 3,578 | 36% |

| AHS Oklahoma | 2,619 | 39% |

| Warren Clinic | 3,028 | 35% |

| Omni Medical Group | 1,780 | 37% |

| Urologic Specialists | 1,133 | 47% |

| Newborn Specialists | 1,924 | 46% |

The organizations contributing the most errors to payers’ directories tend to be large health systems, large group practices, or medical staffing companies. We have observed the root cause of most errors is the over-association of providers to addresses where providers are not regularly seeing patients (or where they may not visit at all). There is a not entirely unfounded understanding among payer enrollment professionals that if a provider submits a claim for an appointment that takes place where a provider is not listed, that the claim can be denied. Some payers employ this rule, resulting in many provider groups associating their practitioners with most or all locations. As provider organizations have an increasing number of practitioners and locations, the ‘opportunities’ for mistakenly associating a practitioner grow exponentially within that organization. Which means that just a handful of very large organizations are contributing the most errors to a payer’s directory. When we ran the numbers, we found that 66 provider organizations represent 50% of all errors contributed to payers’ directories in the state of Oklahoma. Drilling down more strategically, only 6 provider organizations represent 25% of all errors in the state.

What this means for the Oklahoma pilot and for the National Directory

There is ample work to be done. Even after years of investment and interventions, most payers’ directories have experienced only modest improvements. A National Directory pilot will need to significantly boost payers’ directory accuracy in Oklahoma before it can achieve this nationally. Employing analytics on data from payers’ Provider Directory APIs is an efficient and scalable way to measure improvement over time.

It is possible to move the needle in Oklahoma. With large provider organizations contributing the most errors into payers’ directories, the payers can strategically work with these provider organizations to assess best practices and identify the best sources of directory data. There’s no magic bullet around this, and it is painstaking work to promote process change upstream within provider organizations, but with most errors clustering in the largest provider organizations, there is an opportunity at a state level to impact change and lift the accuracy level for all payers’ directories within the state. Results like we produced above could be used as a feedback loop between payers and providers to catalyze a virtuous cycle of data accuracy improvement. As payers present these findings to providers, providers can make the necessary upstream changes to submit the correct data, and payers can also work out the kinks in their ingestion and transformation processes to ensure only the correct data gets posted in directories. The knowledge that this data is readily accessible via API, and that it can be quickly assessed for accuracy, will be a healthy motivator for provider organizations and payers alike to improve.

Provider Directory APIs are a key building block in the NDH pilot as well as the eventual national implementation of the directory. These APIs expose key data from payers where they are the source of truth (insurances accepted). Regulators can use the data from the APIs to monitor compliance and continuous improvement around accuracy. Providers can use findings from analytics on these APIs to collaborate with payers to correct errors wherever they may be found. In preparation for National Directory efforts, it is essential for regulators and payers to ‘finish the job’ around making their Provider Directory APIs usable to solidify this important foundation for a National Directory.